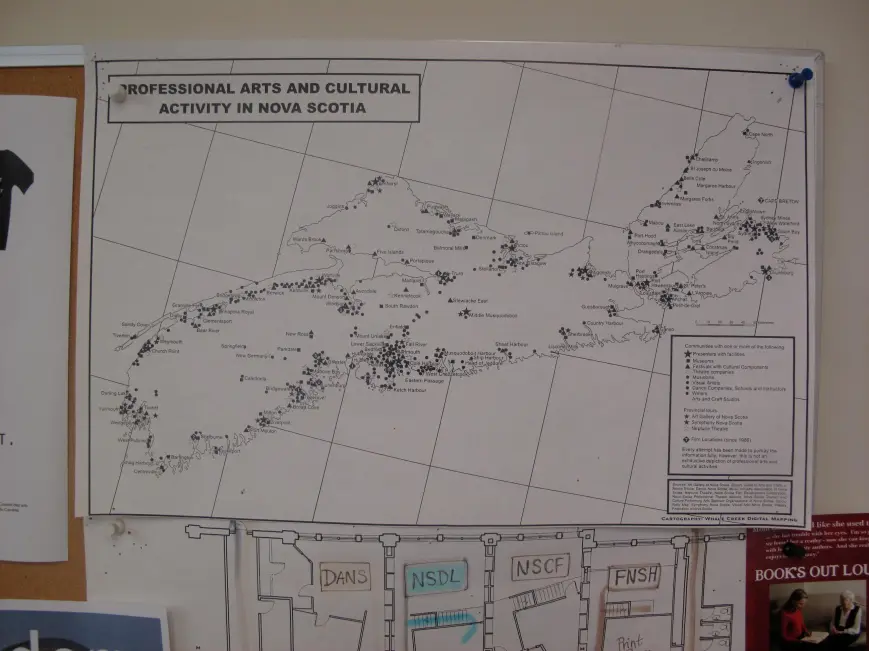

Looking South from Big Intervale to the Sugarloaf (centre-right). Photo taken in the 1930’s by Norman MacLeod, who ran a photo studio in Sydney, CB. Image courtesy of the late William MacDonald.

Directly to the south of the place where I am from, an all-but-vanished settlement at the end of a dirt road, in an ancient fault line that extends the length of Western Cape Breton Island, there is a mountain called the Sugarloaf that rises abruptly from the river valley. Separated from the surrounding highland plateau, a winding dirt road passes around one side of the mountain, and a river flows through a narrow gorge on the other side. Several years ago, my partner Diane Borsato designed a “walking studio,” a building that functions as a mobile field lab for an artist to conceive and reflect on artworks that involve walking. After being located at Don Blanche, an artist residency in the Ontario countryside, and at the Art Gallery of York University, we transported it to Cape Breton and installed it in a grove of birch trees, on a ridge that faces this mountain.

The walking studio is small glass and cedar building with a circular sauna that doubles as a sleeping chamber, and a table for reading, taking notes, organizing specimens, or serving tea. It’s a perfect base for mushroom forays or hiking trips, or to conceive different ways of inhabiting or encountering a landscape. In the winter, when the moon is full, I light the stove and ski around the valley in the moonlight while the sauna heats up. When I was there last, during the summer, I read a book about the Marathon Monks of Japan’s Mount Heiei, practitioners of Tendai Buddhism, and studied topographical maps, thinking of how physical movement shapes how we incorporate and reflect upon the places that we inhabit.

The Marathon Monks can elect to undertake a 1,000-day marathon around 2,700-foot Mount Heiei as part of their spiritual practice. Spanning seven years, this moving-meditation retreat includes running 40 kilometres each day for 100 days, a distance that increases to 84 kilometres for each of 100 days during the seventh year. Wearing straw sandals and white robes, and adopting a gentle, steady gait that makes them appear to be floating through the air, they carry a knife that they must use to commit ritual suicide if they are unable to continue. At the end of this period, after they have run over 46,000 kilometres, they then must undertake a seven and a half day fast without food, water or rest. If they succeed, they are regarded as having achieved enlightenment. Since 1885, only 42 monks, including one who completed it twice, have finished the retreat (Stevens, 1985).

After reading about the marathon monks of Mount Heiei, I went on a much shorter run around the Sugarloaf. The Marathon Monks, who revere nature, often begin their run with a waterfall purification ritual, and stop at temples, shrines and tombs, springs, and other places of spiritual significance for prayer and devotional observation as they circumnavigate the mountain. Running the route around the Sugarloaf, I followed the river down one side of the valley, along a barely traceable hiking trail, to the next community five miles downstream, picked up the paved road for about two miles, and followed a shortcut along a woods road through the forest to the gravel road that continues back to where I started. As a walk it would take all day, but as a run, it took me under three hours; the lazy part of a summer morning, with time to swim in some of the brooks along the way.

I started from the walking studio, passing the farm where I grew up and neighboring farms that, with one exception, have been almost completely reclaimed by the forest. The river wends back and forth across the wide valley, against the far mountain and back again, alongside the road. Then the valley narrows, so the road cuts into the mountainside, and widens again where there is a fishing lodge that faces a waterfall high up on the mountain. Long ago, this property had been cleared for livestock, and then sold sight-unseen in the 1970s to homesteaders who built an octagonal turret-like house. They lived there for the better part of a decade before they finally parted ways, and the house was sold and turned into a restaurant.

Beyond this point there is no road. But there is a path that has been kept clear by the lodge owner for fisherman and hikers, and by a herd of cows that once migrated upriver each summer. Half a kilometer past the lodge, the river swings back towards the mountain and I cross a tiny stream where I can smell wild mint among the rocks, and jog along the riverbank to a place where the valley widens again. In this valley, that was once called MacLean’s Intervale, there is a clearing where there are stones from a foundation, an overgrown apple tree, and a small brook that flows from the mountain. During the second half of the 19th century a couple named Archibald MacLean and Flora MacArthur lived here. I know little more about them than that Flora lived to 110, and that a member of this family experienced a “forerunner,” a vision or dream that described an event that was to happen in the future, a phenomena that was well known among people from this place. In this case, the person envisioned what they described as a tragedy on one the side of the Sugarloaf that would be worse than anything that had happened before. The following summer a daughter of the family was dragged to death by a team of runaway horses. These are the few facts that local historians recorded about their lives (Hart, 1963).

While little was written down, there are many clues to the past that can be discerned from the landscape itself. In the early spring, when there are no leaves on the trees and snow still lingers in the woods and in shaded ravines, it is possible to make out the faint lines of roads cut to haul wood from the mountains. And along the edges of meadows are piles of rocks from fields that were cleared, and scraps of iron or crockery can be found among the ruins of stone foundations. When I come across these faint clearings where the forest opens up and there are signs of human presence, there is a haunting sense of having slipped into another time, where others might also wandering around.

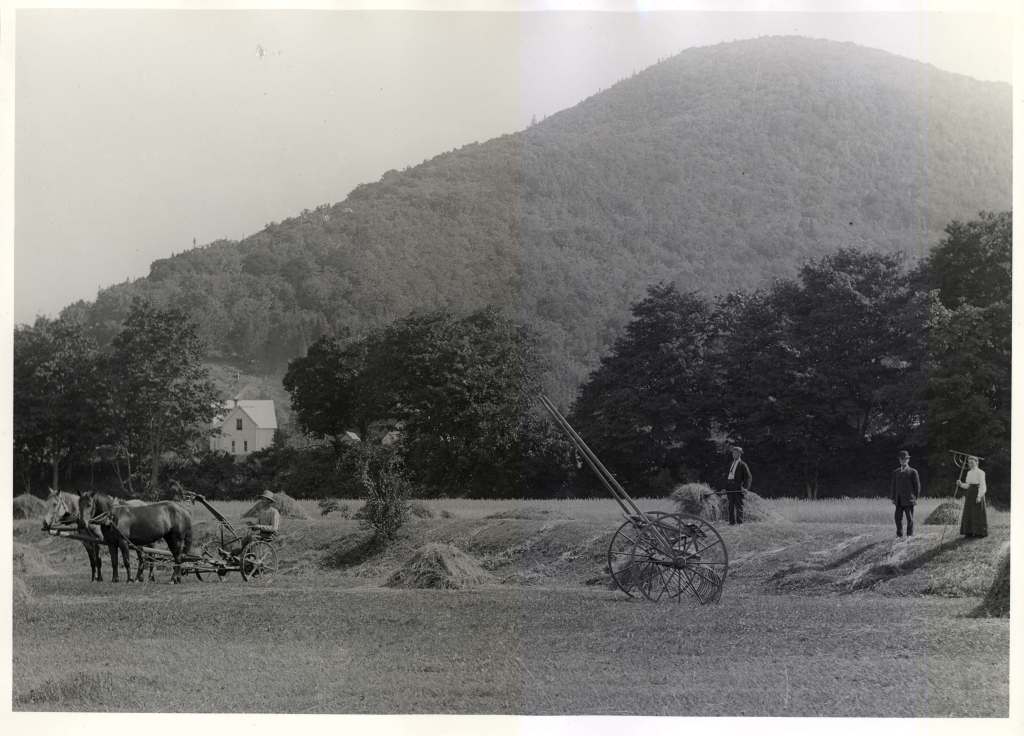

MacLean’s Intervale is full of mature maple trees, and spruce trees covered with large burls – bulbous growths caused by burrowing insects or fungus. Beavers have flooded the lower intervale along the river, making passage difficult. From here I bushwhack through windfalls and find my way downstream to where the river cuts back to this side of the river. Despite these obstacles, the valley is so narrow that it’s almost impossible to get lost. A kilometer downstream are the remains of a cribwork built into the side of the mountain during the 1960s as part of an effort to restore the road. I scamper over boulder and roots to find the trail at the other end of the pool, a well-defined path that leads to the upper farm pastures of Portree and meets the paved road at the end of the bridge, where local kids jump from the bridge into the deep pool below. Below the bridge is a farm depicted in a glass plate negative, from which someone gave me a print, but knew nothing other than where it might have been taken. For years I showed it to anyone who I thought might know what it portrayed and walked around different sides of the mountain, trying to see where it was taken. When people started putting old photographs on Facebook and commenting on them, I posted it to a group that shared images from this area and several people immediately identified it as depicting a farm where in 1912 a two year-old boy mysteriously disappeared. There were various theories: that he’d fallen into the river; that he’d been carried off by an eagle; that he’d been abducted by a traveling salesman or by someone seeking revenge against the family. When my parents came to this place sixty years later, this was an event that was still talked about.

Farm below the Portree bridge, in the late 19th century. Photographer unknown.

Image Courtesy of George Thomas.

What remains of this trail, the one that I followed, goes from the west side of the Portree bridge to the Big Intervale Fishing lodge.

From there, I run along the Portree road, turning onto a tractor road that cuts across the backlands to Rivulet, a place that now consists of only a cluster three houses. I pass by a farm where I worked each spring when I was a student, for a few weeks helping to repair fences and shovel out the cow barn, listening to the father who had lived his entire life there describe things from sixty years earlier as vividly if they’d happened just that morning. He described traveling up the grown-in road that I’d just followed, when it was the main road, to go to dances in places where there are now only spruce trees; about who came to those parties and their different characters and temperaments; and he talked fondly of his wife, who he met there, of how in the summer the cows could smell the cow parsnip on the top of the mountain and would walk all the way up there so they could eat it.

Along the Big Intervale road I settle into a steady pace. The ten-kilometer distance that I’ve only ever covered in a car or on a bicycle passes quickly. I find a gentle physical rhythm, hearing the murmur of streams as I pass over them, feeling clouds of hundreds of tiny insects hitting my skin, smelling the fragrances of flowers and trees, and tasting the cold clear water when I kneel down to drink at a tiny spring hidden along the edge of the road. As I approach Big Intervale, I meet Diane, who has come looking for me in the car, get in, and after a kilometer, get out again so that I can run the final distance. Here, one can feel entirely cut off from the rest of the world: the telephone and electrical lines, and the gravel road all end. Beyond this place is only river and mountains and forest. Inhabited by 80 or so families during the 19th century there are now only about three year-round households. All but a few of the farms that they eked out of the soil have long fallen into ruin and been reabsorbed by the forest. There is a sense of a history that has vanished almost without a trace, leaving memories that can be registered only by being there, as they return to the earth.

At the end of the run, I meet up with Diane and we walk back to the walking studio, passing through the forest where my father once had a sawmill. Down on the ground I see the unmistakable shape of a young porcini mushroom, a prized edible that has an earthy, bodily fragrance. This is the first I’ve found here, and we bring it back to the Walking Studio for identification.

Distance: 20 km.

Time: 2.5 hours.

Sources:

John F. Hart, History of Northeast Margaree (Margaree, NS: no publisher, 1963)

John Stevens, The Marathon Monks of Mount Hiei (Boston MA: Shambala, 1985).

Ashley Tingley, Cold Case of Portree (Pictou, NS: Advocate Printing, 2010).